From Ada Lovelace, the first computer programmer, to 2020 when the majority of software developers are male, gender ratio in IT sure has taken a turn for the worse. What exactly is the history of women in computing (and how did things end up the way they are)?

Programming now and then

If I asked you to think of a typical programmer, what picture would you have in your mind? You’re probably picturing a socially awkward person in a darkened room or even a basement behind at least four computer monitors, am I right? And the gender of this person you’re imagining is almost certainly male. Male, because as of early 2020, 91.5% of software developers worldwide are men, according to statista.com.

If I asked you to think of a typical programmer, what picture would you have in your mind? You’re probably picturing a socially awkward person in a darkened room or even a basement behind at least four computer monitors, am I right? And the gender of this person you’re imagining is almost certainly male. Male, because as of early 2020, 91.5% of software developers worldwide are men, according to statista.com.

What if I told you it hadn’t always been this way? In fact, in its early years, computer programming was a field populated mostly by women. This might ring some bells, and if you think hard about the history of women in computing, you might be able to squeeze your brain and come up with a few names: Ada Lovelace, Grace Hopper, perhaps Stephanie Shirley or Katherine Johnson… maybe… and then… blank. No more names, despite the fact that computing early on was such a feminised form of work that most men did not even dare to go into it. What changed? Well, it was a series of events, to be honest, but the main thing is that, as the field started to increase in importance, male programmers wanted to elevate their job out of the “women’s work” category.

The first computer programmer was a woman

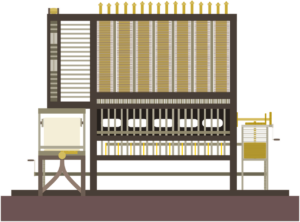

Before we jump to 2020 though, let’s start from what we may call the beginning: Ada Lovelace, an English mathematician mainly known for her work on Charles Babbage’s proposed mechanical general-purpose computer, the Analytical Engine. She basically wrote the world’s first machine algorithm for an early computing machine that existed only on paper. As a result, she is often regarded as the first person to have recognized the full potential of computers and, consequently, she is considered to be the first computer programmer.

Women beat the Nazis in WWII

Allright, that might be an overstatement, but female codebreakers at Bletchley Park, which was then the centre of British cryptanalysis, were essential to an operation which is often said to have shortened the second world war by 2-3 years. Bletchley Park housed the Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS), which regularly penetrated the secret communications of the Axis Powers – most importantly the German Enigma and Lorenz ciphers. And, surprise surprise, three quarters of the workforce at Bletchley Park were women.

Mavis Batey, one of the Bletchley Park women, broke a message between Belgrade and Berlin that enabled Dilly Knox‘s team to work out the wiring of the Abwehr Enigma. Then there was Jane Fawcett, who decoded a message referring to the Bismarck that detailed its current position and destination in France, and therefore helped to sink the ship, making this the first significant victory by the codebreakers. Alongside Jean Valentine, Joan Clarke and other amazingly skilled female codebreakers, the women of Bletchley Park played a very significant role in WWII.

The early 1960s computer scene was still dominated by women

Following WWII, as late as the 1960s many people perceived computer programming as a natural career choice for savvy young women. In an article titled “The Computer Girls,” Cosmopolitan Magazine described the field as offering better job opportunities for women than many other professional careers.

As Grace Murray Hopper said, programming was “just like planning a dinner. You have to plan ahead and schedule everything so that it’s ready when you need it…. Women are ‘naturals’ at computer programming.”

In fact, the number of coding jobs exploded in the ‘50s-’60s as companies began increasingly to rely on software. Back then, since there wasn’t much of a specialized education for computer programmers, employers simply looked for candidates who were logical, good at math, and meticulous. As it turned out, it was mostly women who had possessed these skills.

The dropping numbers

By the middle of the decade the gender ratio started to change, and not long after, women had largely vanished from the field. Not because the work was any different, but, among other things, mainly because the perception of the work had started to change.

If we want to pinpoint an exact moment, it was probably 1984. Up until then, the participation rate of women in computer science programs had risen steadily, by the 1983-84 academic year, 37.1 percent of all students graduating with degrees in computer and information sciences were women. From 1984 onward, the percentage dropped; by the time 2010 rolled around, it had been cut in half.

What changed?

Two sides to every story, three sides to this one: industry, academics, government

The change in the gender ratio can be traced back to changes in three main sectors, each of which contributed to some degree. Some of these were subconscious or even in a way natural, others were very much a conscious choice.

As for industry, it was a change in the attitude toward and perception of jobs in computing . In earlier decades, coding software had not been considered to be as important as the hardware. Hardware programmers—the majority of whom were in fact men—were seen as the heroes, and software programmers—a task considered to be more suited for the female mind—played the supporting role. Later, however, the old hierarchy of hardware and software were inverted. Software was becoming critically important as computers were being integrated into every part of work. As their power became more apparent, women were no longer seen as appropriate for this type of work—nevermind that they had all the skills necessary to perform it. Of course, now that it had actually started to matter and they started to see its importance, men wanted to be part of software development.

These male programmers created professional associations and discouraged the hiring of women. Ads began to connect women staffers with error and inefficiency. They instituted math puzzle tests for hiring purposes that gave men who had taken math classes an advantage, and personality tests that purported to find the ideal “programming type.” Remember, not long before it had been precisely the female stereotypical personality that they considered the ideal programmer. Power can be a strong motivator for acquiring a fresh perspective.

These male programmers created professional associations and discouraged the hiring of women. Ads began to connect women staffers with error and inefficiency. They instituted math puzzle tests for hiring purposes that gave men who had taken math classes an advantage, and personality tests that purported to find the ideal “programming type.” Remember, not long before it had been precisely the female stereotypical personality that they considered the ideal programmer. Power can be a strong motivator for acquiring a fresh perspective.

While the field was changing, employers increasingly hired programmers whom they could envision one day ascending to key managerial roles in programming. Who in their right mind would dare to put a woman in charge of men, am I right?

A less conscious change was happening among academics. It had most to do with the change in how and when kids started to learn programming. Once the first generation of personal computers found their way into homes, kids were able to play around and slowly start learning the major concepts of programming. Those kids were mostly boys who saw their fathers in front of the computer and wanted to follow them. Mothers were typically less engaged with computers in the home, and girls picked up on those cues and even the nerdier girls reined in their enthusiasm. How does this relate to computer science programs at university level? Well, as the importance of the field grew, so did the interest in these programs. However, as they were relatively new, they didn’t really have enough teachers for the increased number of students. Thus, the universities had to come up with acceptance criteria and tests to select the perfect candidates for their study programmes. Inevitably, those who learned basic computing in their childhood were more likely to excel on these tests and gain acceptance to universities to study computer science.

As far as the public sector goes, the tendency with government jobs was similar to what was going on in the industry. As programmers started to become more important and needed to be put into managerial positions, a sudden change of heart could be seen. Let’s look at the British government as an example. Women formed an underclass of highly technically trained and operationally critical technology workers—dubbed “the machine grades” within the civil service. When the British government finally started paying its own workers equal pay for equal work, the majority of these women did not in fact get equal pay: the rationale was that women had been doing this work for so long, and in such great majority, that their lower rate of pay had now become the standard market rate for the jobs. With these different pay categories, refusal to promote them into higher positions, and other techniques, governments had basically started deliberately pushing women out .

One rebel above all

This deliberate removal was the very thing Stephanie “Steve” Shirley had had enough of, and, after having been denied a series of promotions that she had earned, she left the public sector, but, finding the same discrimination in industry, she went on to create her own software company. Her business model was successful, she turned the problems in industry to her advantage: she hired all the talented female workers who were being edged out of their jobs, either through outright discrimination or through government and industry’s unwillingness to provision any kind of maternity leave, childcare, or flexible family-friendly working hours. Instead, she gave them the opposite: flexible hours and the ability to work from home. Did you notice the “Steve” in her name? The only way she was able to be a successful rebel was by using the name Steve professionally in order to cut through the sexism of the industry.

This deliberate removal was the very thing Stephanie “Steve” Shirley had had enough of, and, after having been denied a series of promotions that she had earned, she left the public sector, but, finding the same discrimination in industry, she went on to create her own software company. Her business model was successful, she turned the problems in industry to her advantage: she hired all the talented female workers who were being edged out of their jobs, either through outright discrimination or through government and industry’s unwillingness to provision any kind of maternity leave, childcare, or flexible family-friendly working hours. Instead, she gave them the opposite: flexible hours and the ability to work from home. Did you notice the “Steve” in her name? The only way she was able to be a successful rebel was by using the name Steve professionally in order to cut through the sexism of the industry.

So, here we are today, with a world of computer programmers who are expected to be male, nerdy and antisocial — and most of them simply forgetting the women that the entire field was built upon, but not us. We know.